Marco Polo Tells About Indonesia

Marco Polo's trip to China is one of the most famous expeditions of all time. It took three and a half years, and, along the way, he had to guard against killer bandits, climb the tallest Asian mountains without protective clothing or climbing gear, and cross the Gobi Desert.

Marco Polo spent 20 years in China. When he returned home, he sailed south from China, past Sumatra (where he stayed for five months during monsoon season), through South India, the Indian Ocean, and the Persian Gulf. He then left the sea and set off on land, arriving in Venice in 1295.

In His Own Words

Here are two of Marco Polo's descriptions of what he saw in Indonesia. First, figure out what he is describing. Then predict how the people of Venice reacted to his tales. Were they interested? Scornful?

"... In the country are many wild elephants and animals which are much inferior in size to the elephant but their feet are similar. Their hide resembles that of the buffalo. In the middle of the forehead they have a single horn; but with this weapon they do not injure those whom they attack, employing only for this purpose their tongue, which is armed with long, sharp spines. Their head is like that of the wild boar and they carry it low towards the ground. They delight in muddy pools, and are filthy in their habits...

The Indian nuts also grow here, of the size of a man's head, containing an edible substance that is sweet and pleasant to the taste, and white as milk. The cavity of this pulp is filled with a liquor clear as water; cool, better-flavored and more delicate than wine or any other kind of drink whatsoever."

-- Marco Polo, The Travels of Marco Polo

Manuel Komroff, Editor. The Easton Press, 1934

Think About It

The Venetians thought Marco Polo was crazy to think he has seen a unicorn. And they flatly refused to believe a nut could be the size of a person's head. How could Marco Polo have convinced them?

The Day the Earth Exploded -- Krakatau

Introduction

As early as the fifth century, people were describing the power of Indonesia's volcanoes:

The world was shaken with violent thunderings that were accompanied by heavy rains of stones.

[The volcano] burst into pieces and sank into the depths of the earth.

--Excerpt from the Javanese Pararaton, The Book of Kings, 416 AD

The most dramatic eruption in modern times happened in the summer of 1883, when the sleeping giant, Krakatau, awoke. Krakatau was a volcano on the island of Rakata Besar.

On August 27, 1883, at 9:58 in the morning, Krakatau roared with the loudest explosion ever recorded. It was literally the sound heard round the world, as its sound waves bounced back and forth across the globe for the next five days. The explosion registered a force one million times stronger than the hydrogen bomb. Dust and ash were ejected into the air, remaining so heavy that nearby areas were dark for three days.

After Krakatau's fury was over, whole island had disappeared, thousands of homes were destroyed, and over 36,000 people had died. Most drowned in the tidal waves caused by the volcano.

By 1920, over 800 different kinds of plants and animals could be found on what was left of Krakatau's slopes. It was virtually impossible to hack a path through the dense growth on the island.

Anak Krakatau, "Child of Krakatau", a new volcano, is already over 200 meters high and has

had small eruptions. Scientists predict that someday it may be as fierce as its parent.

--Tom Simkin and Richard S. Fiske, Krakatau 1883: The Volcanic Eruption and Its Effects.

Smithsonian Institution Press, 1983.

Eyewitness Reports

August 27, morning

[There were] rumblings, crashings, and flashes off in the distance ... due, we learned afterwards, to the eruption of Krakatau when it blew its head off and practically the whole island went up in the air ... The air was filled with dust and ashes. The reverberations of the explosions were something unbelievable...

--A boy whose father was captain of a ship

August 27, 11:30 a.m.

By 11:30 a.m. we were enclosed in a darkness that might almost be felt, and then commenced a downpour of mud, sand, and I know not what...

--Captain Watson, on the Charles Bal

August 27, about 2 p.m.

It is so dark here that one's hand cannot be seen when held before the eyes. Krakatau is completely enveloped in smoke.

--The last message received from Anyer before the city was washed

away in a series of tsunamis, or tidal waves, some 120 feet high.

August 27, afternoon

We saw ... a great black thing, a long way off, coming towards us. It was very high and strong, and we soon saw that it was water ... We all ran ... and tried to climb up out of the way of the water ... But all was soon over. One after the other, they were washed down and carried far away by the rushing waters.

--A Javanese survivor, on Merak

I happened to look up and perceived an enormous wave in the distance, looking like a mountain rushing onwards, followed by two others that seemed still greater. I stood for an instant on the bridge, horrified at the sight ... then ran as fast as my legs could carry me. The roaring wave followed us, knocking to atoms everything that came in its way. Never have I run so fast in my life, for, in the most literal word, death was at my heels.

--A visitor on Anyer

Think About It

Why are eyewitness reports of a disaster valuable? Why would some people question their accuracy? If we could devise a way to prevent natural disasters, such as the eruption of Krakatau, should we use it? Why or why not?

Indonesia and the U.S.: Crucial Connections

Trade between Indonesia and the United States began in earnest in the early part of this century, when Indonesia's natural resources met the demands created by Americans' appetite for automobiles.

Start Your Engines

In 1900, automobiles were a luxury in the United States; worldwide, there were fewer than 10,000 cars on the road. By 1914, thanks to Henry Ford's pioneering approach to automobile production, 300,000 Model T's were produced; just one year later, annual production was up to 500,000. The relatively inexpensive Model T and other cars were becoming a necessity for the American public. By the late 1920's, 23 million cars were registered in the United States.

Ask Yourself: What consumable products had to be imported by U.S. automakers?

If you answered gasoline, oil, and rubber, you're beginning to understand the Indonesian connection.

Where the Rubber Meets the Road

American cars took to the roads on tires made of rubber imported from Indonesia and other Southeast Asian countries. Thanks to the unprecedented demand, rubber plantation production in Southeast Asia surged from 4 tons in 1900 to 360,000 tons in 1920.

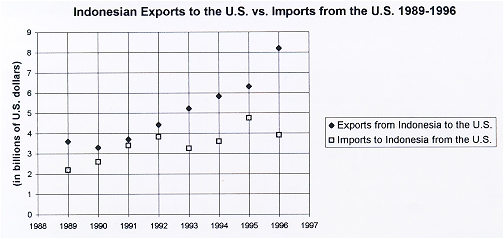

Trading Partners -- U.S. and Indonesia

Oil, gas, and rubber were the traditional Indonesian exports to the United States. But since the mid-1980's, manufactured items such as clothing, footwear, and video components have become important exports. In fact, the U.S. is the largest importer of Indonesian manufactured goods.

Indonesia imports a variety of products from the U.S., including high-tech items such as aircraft, electronic circuits, and TV cameras, and agricultural products such as cotton and soybeans.

Complete the graph by drawing two lines to connect the symbols; the top line will show the value of imports; the bottom will show the value of exports.

Ask Yourself: In which year was the gap between the value of imports and exports greatest? What conditions in Indonesia might have contributed to closing the gap?

Now ask the same question using more recent data below.

Indonesia In the Global Marketplace

Exports

Indonesia exports a variety of its manufactured products and natural resources to world markets. Between 1982 and 1992, Indonesia changed from an emphasis on oil to non-oil exports.

Percentage of Non-Oil vs. Oil Exports 1982-1992

Ask Yourself: What happened to the world market for oil to account for this change? In which year did non-oil exports first surpass oil exports?

Selected Imports from Around the World

Ask Yourself: What were the differences between imports in 1992 and 1993?

Which of Indonesia's trading partners might supply these goods?

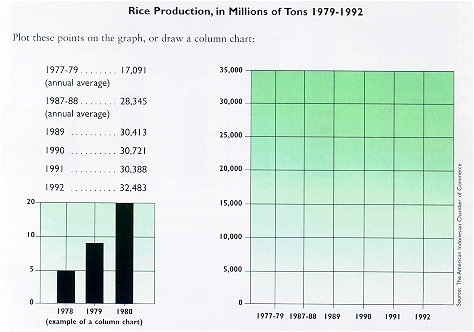

Rice--The Amazing Grain

"There is no wheat produced here, but the people live upon rice."

--Marco Polo, The Travels of Marco Polo

Rice is a staple of the Indonesian diet. In the 1970's, Indonesia imported rice to feed its population. Then the government began a program to grow rice. Through price controls, hard work, and innovative agricultural methods, Indonesia was self-sufficient in rice production by 1985.

Two Ways to Grow Rice

Here are the two methods used by Indonesian rice farmers. List two benefits of, and problems with, each method.

Ladang:

Used wherever the land is dry and its area is great compared to population. The forest is chopped down, and the brush is burned to create ash to supplement the weak soil. This soil loses its nutrients after one or two crop cycles, so farmers move to the next acre. The land must be left fallow for ten years before it can be used again.

Sawah:

Used wherever is very wet land. Hillsides are cut into terraces irrigated by a complex series of canals supplied by ponds and streams. Some fields can generate a cycle of two or three corps a year.

The Art of Indonesia: Batik

Above Pictures from an excellent website on batik: http://www.serve.com/aberges/batikpag.htm

Introduction

Batik is a traditional textile art form found in Indonesia. In no other country has the art of batik been raised to such a high level. In batik, a cloth is painted with hot wax in complex patterns. When the cloth is placed in dye, the color stains all but the areas covered by wax, a dyeing method called wax-resist. By waxing different areas in different dyes, layer after layer of color is added to create amazing depths and complexities in the patterns.

Making Batik

What You Need:

Light-colored blackboard chalk, sharpened to a point with sandpaper

A white handkerchief, washed and ironed to it's wrinkle free (thin cotton or silk is best)

An embroidery frame

Batiking wax (or a mixture of equal parts -- by weight -- of beeswax and paraffin)

Fine-tipped brushes

Rubber gloves

Cold-water dyes or waterproof writing inks (yellow, red, and/or blue)

A nonporous container for the dye (a shallow glass baking dish works well)

Newspapers

An iron and an insulated ironing surface

Sheets of heavy-duty brown paper wrap.

1. First, design your batik pattern. Keep it simple. For your first batik, use a design that only involves the center of your handkerchief Remember, the dye is transparent, so colors will layer over each other. You'll be dyeing from light to dark.

2. Draw your completed design onto the handkerchief, using the blackboard chalk. (A pencil or regular dressmaker's chalk won't rinse out well after dyeing.)

3. Stretch the handkerchief on the embroidery frame. Get a frame size that gives you the most space to work on.

4. Under adult supervision, use a double boiler, or a microwave (set at short intervals), to carefully melt the waxes. Hot wax will scald, so use caution -- and oven mitts. Stir to blend. After cooling, the wax can be reused if it is reheated.

5. Use the brushes to apply wax. You may have to reheat the wax periodically. The areas you wax will resist the dye and remain white after your first dip into the dye.

6. Allow the wax to dry, being careful not to wrinkle the cloth, since any cracks in the wax will allow dye to pass through. When the wax is dry, prepare the container with your first dye, the lightest color -- in this case, yellow.

7. Dip the handkerchief in the dye bath, being careful not to wrinkle it. Use rubber gloves to protect your hands. The longer the handkerchief is left in the dye, the deeper the color will be. When the handkerchief has reached a shade you want, move it to a newspaper-covered tabletop to dry. Wash and dry your container for use with the next dye color.

8. After the cloth has dried, do this to remove the wax: Place two layers of brown paper on an insulated surface or ironing board. Stretch the cloth flat on top and cover with two more sheets of paper. Iron with a hot iron. (Do this only under adult supervision!) The wax will melt and stick to the paper.

9. If you are using a second color, you'll need to apply wax in the new areas called for by your design. Follow steps 3 - 8. Repeat for a third color. After the cloth dries for the last time, iron once more to reveal your final pattern. Are the color layers what you suspected?

--Adapted from Francis J. Kafka, Batik, Tie Dyeing, Stenciling, Silk Screen, and Block Printing. Dover, 1959.

![]()